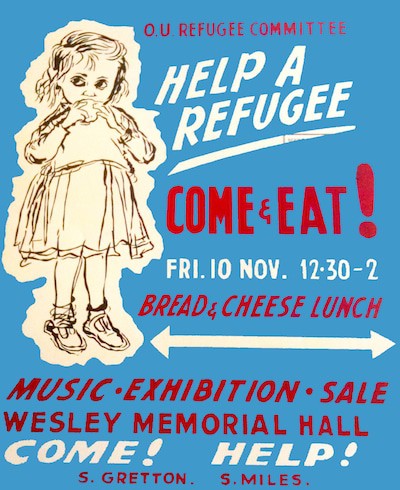

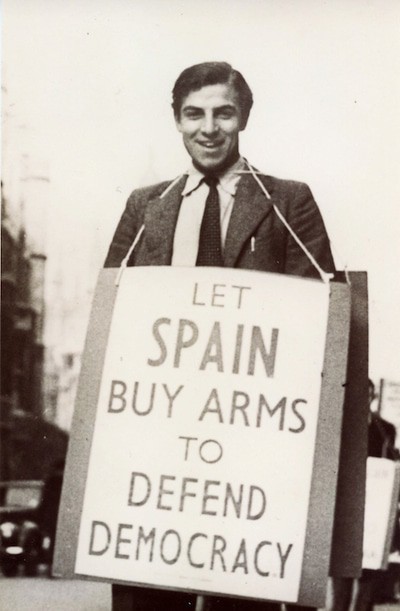

Today, we are proud to be sponsoring the launch of a new study into the history of our sector: Dr. Georgina Brewis’ century-spanning A Social History of Student Volunteering: Britain and Beyond, 1880-1980. In this blog you can see a few of the images which illustrate the diversity of this history.

This evening at the Institute of Education in London we will hear from the author alongside Dr. Justin Davis Smith, Executive Director of Volunteering and Development for NCVO, social historian Professor Carol Dyhouse, and myself.

This is a crucial time for the student social action sector. After decades in which we’ve navigated cycles of funding and cuts, boom and bust, we are now entering a new era of investment in the youth social action movement.

Step Up To Serve, an initiative established in 2013 by request of the Prime Minister, has committed to double the number of young people involved with social action in the UK by 2020. Working with students at the top end of the initiative’s 10-20 age range, our activities are tied up with this ambitious pledge.

To achieve such a positive level of youth social action is going to take serious commitment over the next 6 years. And no more so than in the higher education sector, where support for student volunteering and social action has been a tale of highs, lows and treading water.

Inspired by Dr. Brewis’ book, we have produced our own brief study of student social action – summarizing the key learnings we have distilled over the last 7 years of Student Hubs, and bringing the student movement narrative up to the present day.

As a relatively young organization, we are standing on the shoulders of giants: with decades of research and knowledge in existence, it is fascinating to look back and review the pieces of the puzzle which have fed into our culture and ethos, inspiring our model of student-leadership and critical engagement.

However, we’ve also learnt implementation is the curse of our sector. While there is reams of analysis, discussion and dissection of policy recommendations, it has done little to increase the proportion of student volunteers in the UK above more than 30% or so. This in comparison to North America, where figures estimate that 45-70% of young people undertake some form of formal volunteering during their time at university. This level of student participation also positively correlates with higher proportions of adults who continue to volunteer throughout their lives.

We need to combine this level of participation with the critical engagement which will equip students to graduate as citizens of the world with a mission to change it for the better.

The work of Generation Change and Step Up To Serve has created a set of quality principles which are to be the hallmark of all effective youth social action going forward. These will ensure that ‘double benefit’ becomes reality rather than rhetoric.

Double benefit is more than students clocking up community volunteering hours in exchange for coveted CV points. It is about giving students the opportunity to critically engage with the issues they are tackling through their action; and to use this awareness to effect sustainable change for their causes and formulate their own social action identities for life. The double benefit model puts people and impact at the centre of all social action.

Our brief study, launched today to accompany Dr. Brewis’ history, is a call to action to entrepreneurialism, innovation and collaboration in our sector in order to reinvigorate a strong, sustainable and dynamic student volunteering and social action landscape which delivers this model of meaningful and impactful student social action.

The full report can be read here. The key recommendations which we have highlighted from historical and contemporary research are:

- Support for student social action should not be beholden to boom and bust. We need to hold a cross-sector review of how national support can be sustainable and reliable long into the future.

- National infrastructure and frontline delivery organisations should exist to guide, support and incubate student leadership in social action. A tri-annual audit of the state of student led volunteering should be conducted both locally and nationally.

- A review should be conducted to look at barriers to the uptake of ‘service learning’ in the UK.

- To encourage more students to volunteer, we need to appeal to their interests, skills and desire to make a difference. Even if enhanced employability can be a positive outcome of volunteering for individuals, these messages should not be overemphasised to increase levels of involvement.

- A range of tailored approaches should continue to be supported. No one-size-fits-all model can be adopted but setting more common standards of impact measurement would help raise the quality of provision at different institutions

I very much looking forward to discussing this study with many of you in the future. In the meantime, I hope to see you this evening at the launch of A Social History of Student Volunteering.